Metformin has been prescribed to people with type 2 diabetes to manage blood sugar for more than 60 years, but scientists haven't been exactly sure how it works.

A recent study suggests it works directly in the brain, which could lead to new types of treatment.

Researchers from the Baylor College of Medicine in the US identified a brain pathway that the drug seems to work through, in addition to the effects it has on biological processes in other areas of the body.

"It's been widely accepted that metformin lowers blood glucose primarily by reducing glucose output in the liver. Other studies have found that it acts through the gut," says Makoto Fukuda, a pathophysiologist at Baylor.

"We looked into the brain as it is widely recognized as a key regulator of whole-body glucose metabolism. We investigated whether and how the brain contributes to the anti-diabetic effects of metformin."

Watch the clip below for a summary of their findings;

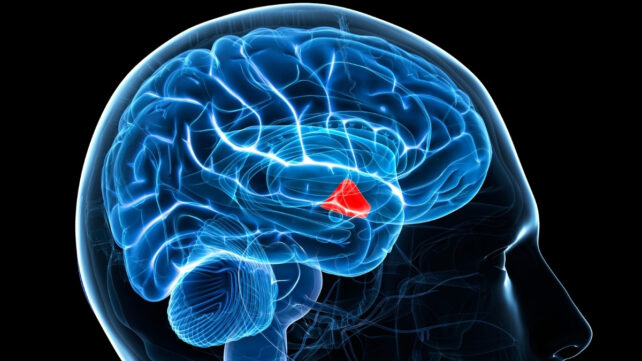

Previous work by some of the same researchers had identified a protein in the brain called Rap1 as having an impact on glucose metabolism, particularly in a part of the brain called the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH).

In their 2025 study, tests on mice showed metformin traveling to the VMH, where it helps tackle type 2 diabetes by essentially turning off Rap1.

When the researchers bred mice without Rap1, metformin then had no impact on a diabetes-like condition – even though other drugs did.

It's strong evidence that metformin works in the brain, through a different mechanism than other drugs.

The team was also able to take a close look at the specific neurons metformin was affecting. Further down the line, that could lead to more targeted treatments that take aim at these neurons specifically.

"We also investigated which cells in the VMH were involved in mediating metformin's effects," says Fukuda.

"We found that SF1 neurons are activated when metformin is introduced into the brain, suggesting they're directly involved in the drug's action."

Metformin is long-lasting and relatively affordable. It works by reducing the glucose produced by the liver and increasing how efficiently the body uses insulin, helping to manage the symptoms of type 2 diabetes.

Now we know it very probably works through the brain, as well as the liver and the gut.

Clearly, this needs to be shown in human studies as well, but once that's established, we might be able to find ways to boost metformin's effects and make it more potent.

"These findings open the door to developing new diabetes treatments that directly target this pathway in the brain," Fukuda says.

"In addition, metformin is known for other health benefits, such as slowing brain aging. We plan to investigate whether this same brain Rap1 signaling is responsible for other well-documented effects of the drug on the brain."

This also ties into other interesting studies that have found the same drug can slow brain aging and improve lifespan. With a better understanding of how metformin works, we may see it used for a broader range of purposes in the future.

Though generally safe compared to other treatments for type 2 diabetes, side effects aren't uncommon, with gastrointestinal problems such as nausea, diarrhea, and abdominal discomfort affecting up to 75 percent of those taking the medication. Other consequences can emerge in association with conditions such as kidney impairment, which also put health at risk.

Metformin is also considered a gerotherapeutic: a drug able to slow down various aging processes in the body. For example, it's been shown to limit DNA damage and promote gene activity associated with long life.

Previous studies have shown that metformin can reduce wear and tear in the brain and even reduce the risk of long COVID.

A 2025 study on more than 400 postmenopausal women compared the effects of metformin and a different diabetes drug called sulfonylurea.

Those in the metformin group were calculated to have a 30 percent lower risk of dying before the age of 90 than those in the sulfonylurea group, demonstrating the drug's potential role in reducing the effects of aging.

Understanding how the drug affects the human body as a whole could inform specialists' decisions in prescribing the drug beyond use for diabetes, and potentially help improve its safety even further.

"This discovery changes how we think about metformin," says Fukuda. "It's not just working in the liver or the gut, it's also acting in the brain."

"We found that while the liver and intestines need high concentrations of the drug to respond, the brain reacts to much lower levels."

No comments:

Post a Comment