On the shores of Lake Erie, in Cleveland, the United States, there once stood a giant steel sphere sixty-four feet tall. Inside the sphere were 38 rooms where Dr. Cunningham’s patients spent up to two weeks at a time breathing air at twice the atmospheric pressure. Dr. Cunningham believed that the higher air pressure introduced oxygen in abundance into the body system and aided in the therapy of various diseases. This is known as hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

Hyperbaric therapy was first documented in 1664 by the English physician Nathaniel Henshaw who wrote about the benefits of fresh air and its medical value in the treatise Aero-Chalinos. Henshaw purportedly built the first hyperbaric chamber two years previously. But Dr. Cunningham was the true pioneer of this snake oil therapy.

Dr. Cunningham had observed in his capacity as an anesthesiologist at the University of Kansas that many patients suffering from lung diseases seemed to improve when they changed altitude and moved from Denver to Kansas City. He concluded that the improvement was due to the increase in oxygen at a lower altitude.

During the 1918 influenza epidemic, Dr. Cunningham built the first hyperbaric chamber—a long cylindrical tank lying on its side with beds inside for the patients—in Kansas City and began treating patients suffering from respiratory diseases. Two early successes with two seriously ill pneumonia patients boosted Dr. Cunningham’s confidence and he began advocating oxygen therapy for nearly every ailment—diabetes, cancer, anemia, pneumonia, hypertension, syphilis. The unorthodox treatment was based on the false premise that these diseases are caused by anaerobic bacteria—bacteria that thrive in oxygen deficient environment such as inside your guts. Therefore, by increasing the oxygen, the bacteria will fail to grow and eventually die off.

One of Dr. Cunningham’s patients who benefitted from the treatment was the millionaire Henry Timken. Some say it was Timken’s friend who underwent treatment. In any case, Timken had enough confidence in Dr. Cunningham’s methods to pledge $1.5 million, a princely sum at that time, for the construction of a hospital and a large hyperbaric chamber in the shape of a steel sphere on the lakeshore in Cleveland, Ohio. The site was chosen because of its quietness and beauty of the surroundings.

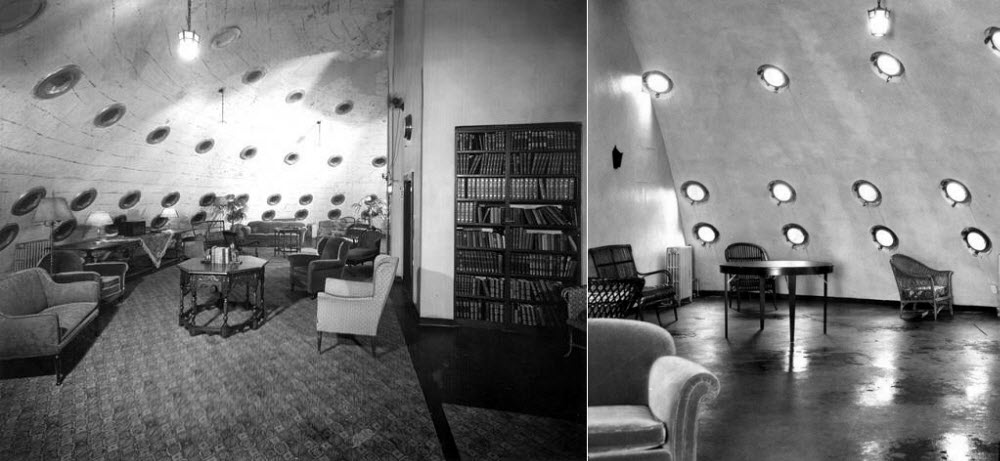

Although the steel sphere looked like an industrial gasometer, the interiors were as luxurious as a hotel with five stories of bedrooms, recreational areas and lavatories. At the heart of the facility was a powerful air-conditioning machine consisting of three compressors, two heating boilers, a 27-ton ammonia compressor that worked as a dehumidifier and various air filters allowed for a precise control not only of pressure, but also temperature, humidity and exchange rate of the air in the facility. The entire system was regulated and controlled by thermostats that automatically adjusted the properties of air within the tanks.

The facility opened in 1928. The same year, the American Medical Association (AMA) Bureau of Investigation published a scathing article questioning whether Cunningham’s treatments seemed “tinctured more strongly with economics than with scientific medicine.”

Five years after the hospital’s opening, the depressed financial status of the country forced Cunningham to sell his hospital to James Rand Jr., son of one of the cofounders of Remington Rand and protégé of Cunningham, in 1934. Rand renamed the facility the Ohio Institute of Oxygen Therapy, but it failed to attract patients, forcing James Rand to sell again 1936. The new owners abandoned the oxygen therapy and converted it into a general hospital. This also closed quickly due to financial problems. The site remained unused until purchased by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Cleveland. In 1942, the hospital building was demolished and the steel ball was dismantled and scrapped for the war.

Dr. Cunningham died in 1937. His methods found no evidence of curing any of the diseases he targeted. However, some of his approaches were validated years later, and found application in special cases such as in the treatment of decompression sickness.

No comments:

Post a Comment