ALI WAS 13 the first time he saw American soldiers. In 2003, as U.S. and British troops rolled into his hometown of Basra, Iraq, he joined his family and neighbors on the street to gape at the procession of Humvees and hulking tanks. As a young boy, he had only the vaguest notions of the geopolitics involved – but he sensed an atmosphere thick with tenuous excitement. “The war was a total shock,” Ali recalls now, speaking over Skype from his apartment in southern Iraq, “but there was a hope that things would be better — that’s what the adults were saying — that things without Saddam would be better.”

By 2006, the foreign troops had become a fixture in Basra, and Operation Iraqi Freedom had cost, by one estimate, as many as 600,000 Iraqi civilian lives. As the country sank into violent turmoil, the community’s initial welcome gave way to resentment, and Ali’s boyish fascination morphed into disappointment. “When they came, with their big weapons and strange language, they were promising to help us make a new Iraq,” said Ali, whose full name The Intercept is withholding for his protection. “But all that came was fighting.”

Ali was in 10th grade when an older family friend told him about his work as an interpreter for the U.S. military. The young man was intrigued. The work of interpreting between the two groups appealed to him. By then, he’d developed a partial theory about the war: “So much of the violence came because these two sides, the Iraqis and the Americans, did not understand each other. I thought, here is something I can do to help both sides. Here is a way I could build peace, help build back my country.”

At 16, Ali quit school and left home for the front lines of a rapidly deteriorating conflict. Ali left quietly, hopefully, bidding his nervous family farewell. When he next saw them, years later, it would be as a fugitive, in hiding from Iraqi militias seeking vengeance for his “betrayal” as an American ally. Soon after, the young man who had hoped to help carry his country into a democratic future would be driven from Iraq, and into a long struggle to find refuge from his would-be assassins.

A

Today, 12 years after beginning his work with U.S. troops, Ali is stranded in Iraq, where threats against his life persist. His hopes are set on a sliver of American visas set aside for people like him, who, after risking their lives to help the United States, now face threats of violence, kidnapping, and death for their efforts. Yet even this tenuous lifeline may be out of reach under a new U.S. president who has shown hostility to refugees at every turn.

The U.S. government has never kept a centralized record of the “locally engaged staff” employed in American effort in Iraq, mostly through contractors and for modest pay, says Betsy Fisher, policy director at the International Refugee Assistance Project. Fisher, who has long worked on Ali’s case, estimates the number of these local staff is in the “tens of thousands” — one contractor alone had hired out 8,000 Iraqi interpreters by 2009. A congressional budget report in 2008 estimated that 15,000 Iraqis also worked as private security contractors for U.S. personnel, and roughly 70,000 total were attached to U.S.-sponsored operations, including aid work.

In recognition of the extreme and particular threats faced by local partners like Ali, the U.S. government created special visa programs for them beginning in 2008, but the process has been been fraught with problems since its inception. Underfunded and slow-moving, the backlog for one of these visa pipelines is at 58,000 and growing.

But the programs’ gradual dissipation has taken on new urgency now, amid the outright assault on refugee resettlement inaugurated by Trump. The president functionally blocked all Iraqis for the first year of his presidency through his “Muslim bans,” but even after the bans lifted, Iraqi refugee applications remain virtually halted, prompting refugee advocates to call it a “de facto ban” on citizens of that country.

After serving the U.S. military for years, the news of the travel and refugee bans, and the president’s rhetoric about his country and religion, were a stinging blow to Ali. “Do they really think this way about us?” he asked. “I am not a terrorist — I am trying to escape the terrorists!” Democratic Rep. Earl Blumenauer, who worked on the original special visa bill, told The Intercept that breaching the trust of men and women like Ali will seriously undermine American national security. “We rely on thousands of local partners all over the world,” he said. “If we become known for abandoning them, after they’ve risked their lives for us, we lose those valuable allies.”

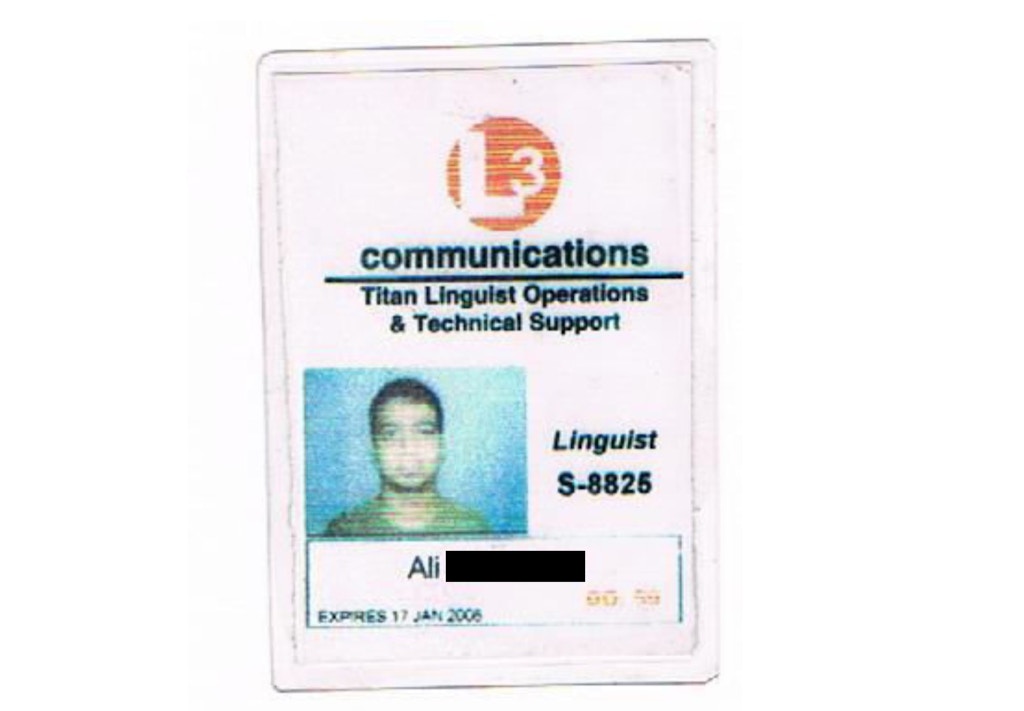

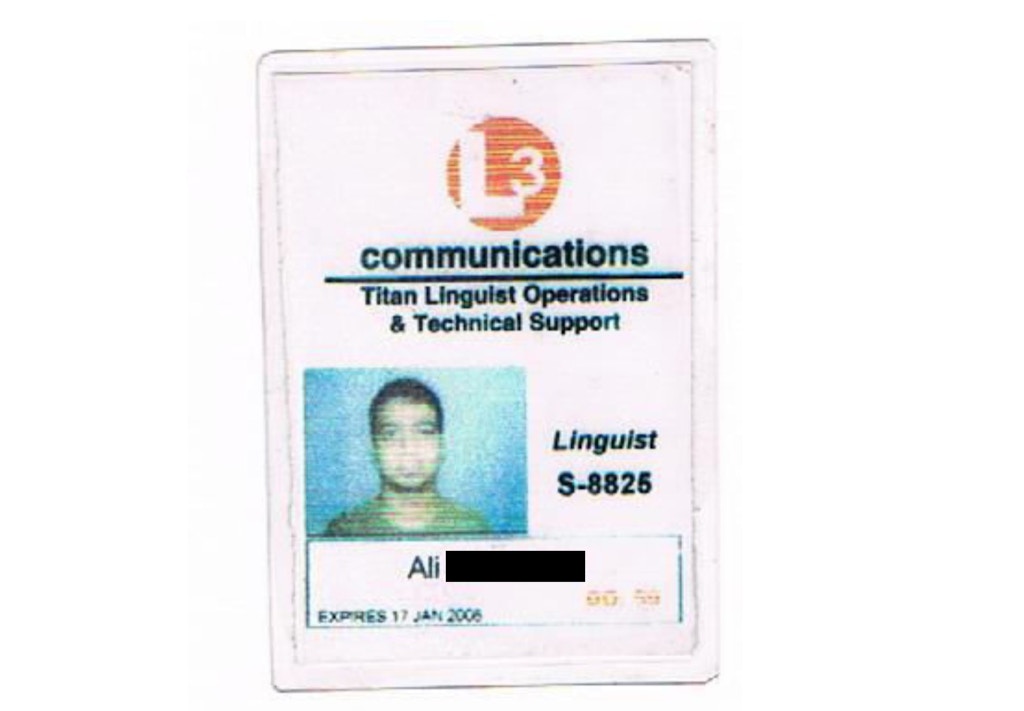

THE WORK AWAITING Ali was grueling. He worked first as a translator in the notorious Camp Bucca, where he was paid $1,200 a month to interpret between Americans and their Iraqi inmates. He recalled the environment as “oppressive, dark, and difficult,” and was disturbed by the conditions and his interactions with the prisoners. Seven months later, at his request, he was transferred to Anbar province to work as a translator for the U.S. Marines at their base in Haditha, 400 miles from his Basra home.

Upon arrival, the young man was dressed in military uniform and assigned lodging alongside American troops. He spent his days in Humvees or on foot with the soldiers as they patrolled “hot” zones, where live fire from local militia erupted unexpectedly from civilian streets. A few months into his post, a roadside bomb blew up one of the vehicles in Ali’s patrol. The sight of the destruction — and the U.S. soldiers killed in the blast — shook him deeply. “I had never seen anything like this before,” he recalled, “I was frightened, of course, but I felt, I can’t quit now. We have to find out who did it.” (To Ali’s knowledge, they never did.) Ali was lucky to evade injury himself — interpreters, placed in combat alongside their employers, were frequently killed and maimed on the job. While the government does not track the number of dead or injured Iraqi allies, one company alone noted over 600 casualties in the years 2003-2008 alone, and Fisher estimates the total to be in the thousands.

Ali’s supervisors noted the young man’s earnest determination to assist the U.S. mission. Officer in Charge J.B. Ellis noted in a 2007 letter of recommendation for him that

Ali has also sacrificed his own personal safety and well being for the Marins [sic] and American civilians around him by serving in every capacity that the Marines do. Despite that potential danger of associating with and working directly for Coalition forces in Iraq, “Ali” persists because of his love for country and dedication for the mission at hand … [he] often volunteers to do missions when other linguists refuse. He has never let down the Transition Team in any task.

The death threats began in 2007. Strongmen from the Jaysh al-Mahdi militia (or “Mahdi Army”) came to Ali’s family home in Basra, asking for him. They made clear that the “infidel mercenary” would pay for his sin — and so would his family, if they failed to produce him. They returned several more times to repeat the threats, underscoring their message by firing bullets at Ali’s family’s home.

Ali instantly recognized the gravity of the threat: Jaysh al-Mahdi had already killed dozens of interpreters in Basra. He was devastated at the thought that he’d endangered his family, but felt helpless to deflect the wrath of the militia. “Now I knew, I had a black stain on me,” he said. “People would not forget this. Even if I quit, they would not forgive me.” Working with the Americans was all he’d known of adult life, and as a marked man without a high school diploma, Ali feared that he’d never find other work. “If I could not protect my family from Jaysh al-Mahdi directly, maybe I could protect them by helping work for peace,” he said. He decided to stay on at the base.

In November 2007, Ali received a call from his brother. On the other end of the line, his voice wavered with panic. Their father had been kidnapped by Jaysh al-Mahdi, who had promised to kill the older man unless his son turned himself over. For two agonizing weeks, Ali and his brother attempted to negotiate for his father’s life. Eventually the militia asked for a ransom of $10,000. Ali paid the sum — most of his savings — and waited for news of his father’s release. A few days later, his brother called again. Jaysh al-Mahdi had lied to them. Their father was dead.

“There are no words for this experience,” Ali recalled. “The world went black. I felt it was my fault that my father was killed. And I was very afraid.” Attending his father’s funeral was out of the question; people in Basra were still searching for him, he said. Alone with his loss, Ali threw himself into his work, clinging to a now-faded hope that his efforts would bring his country closer to peace.

Then, in August 2008, Ali was abruptly fired from his post. His superiors gave no reason, he said, and many of them would later write him glowing letters of reference. But he was told he would have to go. The young man’s fear mounted. While on staff with the Marines, he’d at least had some semblance of protection; now, he was utterly on his own. He hid himself briefly at a relative’s house, communicating furtively with his family, who informed him that Jaysh al-Mahdi was still on the hunt for him. He decided to flee. “When I took the job with the Marines, I never dreamed I’d leave Iraq,” he said, “but now I had no choice. I was not safe. There was nothing else for me.”

Ali landed in Amman late in the night on February 27, 2009. Stepping off the plane and into Jordan’s colder, northern climate, he shivered, surprised as frigid winter rain seeped through his lightweight clothing. With no contacts in the country, Ali quickly reported to the U.N. Refugee Agency, joining 1.7 million fellow Iraqis who had already received official refugee status by that year. Unable to work legally, he took intermittent jobs in construction and food service, rented a drafty flat with a few other Iraqis in the Jabal Al-Hussein district of Amman, and watched his savings evaporate.

Humiliated, broke, and wracked with guilt over his father’s death, Ali struggled to imagine a future. “I felt hopeless,” he said. “I could not go home, and I could not make a life in Jordan. I thought maybe if I could get to the U.S., I could be safe, I could make something of my life.” Online, researching paths to immigration, Ali stumbled onto a description of the Special Immigrant Visas for Iraqis program, whereby Iraqis who had been employed by U.S. Forces, and feared for their safety as a result, could apply for refugee visas through an expedited process. “I was so happy!” Ali said. “It was a program just for people like me!”

THE SPECIAL IMMIGRANT Visas for Iraqis program, or SIV, was the fruit of efforts by advocates and veterans who, beginning in 2006, demanded a government response to the rising casualties suffered by the U.S. military’s Iraqi (and Afghan) partners. Hundreds of U.S. citizens, former military personnel, and diplomats called on the military and Congress to recognize the country’s moral obligation to their local partners who now faced danger and death as a result of their service. Some warned that America risked repeating the ghastly legacy its abandonment of over 150,000 Vietnamese partners in 1975. As of 2006, only 50 visas were allotted per year for Iraqi and Afghan interpreters altogether, and that year only 202 total Iraqi refugees were admitted to United States, of the roughly 4 million displaced worldwide.

In 2008, Congress eventually enacted the Refugee Crisis in Iraq Act, or RCIA, a bipartisan bill spearheaded by Sens. Ted Kennedy and Gordon Smith, which established two pathways for expedited visas. Originally, 5,000 visas per year were allotted to the SIV program, tailored to former employees of the U.S. military, while the second wing of the program, the Direct Access Program, cast a wider net, allowing for Iraqis who assisted other American-led initiatives, such as NGOs and the media, to apply.

From the beginning, these programs were rife with dysfunction. “The program never got the proper funding or appreciation it deserved,” said Rep. Eric Blumenauer, who worked closely with Kennedy and Smith on the bill. “I didn’t see many people really taking to heart just how much these Iraqi and Afghan partners risked for us. Yet, whatever you think of the war, these people have been essential and we have a responsibility to protect them.”

In the first year, only 172 of the possible 5,000 visas were awarded, and it took a long time to resettle even those few. Kirk Johnson, founder of the List Project to Resettle Iraqi Allies, which advocates for wartime allies in Iraq, believes political opposition played a role in the delays. According to Johnson, staffers in the Bush administration who had opposed the visa programs “basically killed [the bill]” by deliberately creating a “very narrow consular interpretation” of eligibility. Even under the Obama administration, however, SIV applicants faced severe delays, often exceeding three years.

Betsy Fisher of IRAP, who has worked directly on dozens of such cases, describes a process that can border on farcical: “I’ve seen clients asked for the same piece of information — a phone number or birth certificate — four or five times after they’ve already submitted it. After resubmitting, they’ll often have to wait weeks before getting an email — asking for them to submit the same thing.” Other Iraqis struggle to come up with appropriate employment documents, often because contractors keep poor records of their Iraqi employees, or because they are unable to get access to a specific, high-level boss — a requirement that one former Army captain told the New York Times was like “a junior associate at a Fortune 500 company asking the chief executive for a letter of recommendation.” As a result of these delays, thousands of SIV visas went unused. By the end of 2011, the year Ali submitted his first SIV application, only 3,415 former Iraqi interpreters had received an SIV — out of a potential 20,000 allotted to the program up to that point.

The second path created by the RCIA, the Direct Access Program, represents an even bigger bottleneck: By 2014, the program had a backlog of at least 38,000 applicants. The DAP process functionally shut down that year, however, when the U.S. evacuated its embassy in Iraq out of fear from the rising threat of the Islamic State, removing the staff members who would have conducted in-person interviews of applicants. Fifteen years after the U.S. invasion, noted IRAP in a March 2018 report, “neither [SIV or DAP] offers a meaningful avenue to escape danger in Iraq.”

On his end, Ali spent hours refreshing his application page on the State Department website, waiting desperately for an update on either of his cases; by then, he’d also applied to the DAP program. In 2011, he received initial approval for his SIV application, but it was quickly revoked. “I was told I was a national security risk,” he recalled, “I thought this was … funny. I know myself. I’m not a danger to anyone! How could I be a danger to national security?” He appealed the decision — and was again denied.

By his third year in Amman, Ali was completely broke. After his rejection from the SIV program, he had little hope that his DAP application, pending for over two years, would be accepted (he would not receive his initial answer — a denial — until 2015). “I had nothing left. The U.S. rejected me, and there was no life for me in Jordan. I thought, even if there is death in Iraq, I want to go home.” He returned to Iraq in 2012. Still fearing for his life, he rented an apartment far from his old neighborhood and kept indoors. “I felt like a stranger,” he said. “Even my family saw me differently.” Hanging over him, always, was his father’s memory, and the guilt he carried about his death.

Ali soon realized there was no future for him in Iraq, either. “My country was destroyed, and I was like a prisoner at home, always afraid for my safety. I realized I could not stay.” Bracing himself, he reapplied to the SIV program. “I thought, ‘I am more than qualified. I worked for the U.S. for over two years; it is only right that they help me now, since I am in danger because of them.’” He filed another application in July 2013 and waited over a year for a response. It came in October 2014, as a form letter with a box checked: He’d been denied again. He was ineligible, the letter said, because the screening of his case revealed “derogatory information.” However, it went on, “the information leading to your denial cannot be shared with you due to its sensitivity.”

Ali was baffled. He thought perhaps there was a mistake — once, while working in Anbar, he’d been detained and interrogated for eight days, only to learn later that the whole thing had been a mix-up. “There was another man in the city with the same name as me, and I think they meant to interrogate him,” he said. Could this mistaken detention have been the reason for his denial? At that time, Ali met representatives from IRAP, who offered another possibility: The ransom he’d paid in an attempt to save his father could be construed as providing material support for terrorist organization.

“The ‘derogatory information’ is a common category given for a denial, but it is very difficult to determine what the basis may be,” says Fisher. “Anything can be used to disqualify someone — for example, if an interpreter is asked to interpret a negotiation with an insurgent, they may use their phone to place the call. Iraqi employees are screened every six months, and when they’re taken in [for] their polygraph, their phones are confiscated and information taken. Having those numbers on their phone may be used against them later.”

Ali was discouraged by the second denial, but this time, IRAP lawyers helped petition his case, filing a 50-plus page appeal, which included eight letters of recommendation. The file was reopened in April 2015.

CONGRESS ALLOWED THE SIV program to expire in 2014 by declining to renew funding. Although a few attempts had been made to improve the program, in total, fewer than 8,000 of the nearly 30,000 potential visas had been awarded. The government promised to complete all applications already submitted before the expiration date, which would include Ali’s pending case. However, as of 2018, his and roughly 100 other SIV cases remain unanswered. Meanwhile, the backlog in the DAP program hovers around 60,000 (Ali is among this number, too).

As Ali waited for word on his two pending applications, he watched as a new militant group, ISIS, ripped through his already-ravaged country. “It made many Iraqis feel more danger,” he said. “We felt anything could happen.” For anyone with ties to the U.S., the rise of ISIS was doubly menacing. Even after the U.S. Embassy evacuated their American staff, functionally halting the DAP process, Iraqis continued to apply at a rate of 2,000 a month, adding to the virtually stagnant pool.

The endemic bureaucratic delays in the visa programs, however, were about to be drastically compounded. Beginning with Executive Order 13769 — the first “Muslim ban” — on January 27, 2017, through late January 2018, Trump effectively blocked all Iraqi refugee processing, says Fisher. And even in the few months since the lifting of the explicit bans, processing of Iraqi refugees remains at a virtual standstill. As of March 31, 2018, only 106 Iraqis had been admitted in the first six months of the fiscal year — as opposed to roughly 20,000 at the same point in FY2014. At this rate, the DAP backlog alone would take over 200 years to clear.

In a statement to The Intercept, a State Department official insisted that “the program is not halted,” and “there is no bar on any nationality, including Iraqis.” The official added, “We take the threats which are posed to [U.S.-affiliated Iraqis] very seriously. We are committed to providing efficient and secure SIV processing while maintaining national security.” The Department of Defense declined to comment.

The delay could also be a result of the unspecified “additional screening measures” imposed by Trump for refugee applications from 11 countries, including Iraq. So far, the administration has refused to specify what these additional measures would be, but advocates are pressing for this information in court. Meanwhile, Trump also slashed the overall number of refugees to be admitted from around the world to a record low of 45,000, and is far behind schedule to meet even this low bar. “Taken together,” said Fisher, “I think this all shows the administration is committed to dismantling the U.S. refugee program writ large.”

As he enters his ninth year of the application process, Ali’s long patience is faltering. “I just want an answer, even if it is no,” he said. “When you are always waiting, it is torture. You don’t know if you should start a family or get a new job; you are always waiting for life to start.” Ali did get married, in 2016, but says he and his wife are waiting to have children. “We don’t know what the future will bring. I am checking my application every day on the State Department website. I think I am a little obsessed.”

Ali thinks often of his choice, in 2006, to join the American mission. “Back then, I believed there would be peace and democracy for my country,” he said, “but now, I wish only that I could go back in time and change my decision. I would finish school, and my father would be alive, and I wouldn’t have to live like this, always in fear, waiting for my life to begin.” If he’s denied once more, he says, “I will appeal again…I will keep trying to the end. Because I am not a threat to America. I want everyone to know that.”